Just because my Beloved died in the Tweed River, I do not want to vilify it.

It’s only a river. Doing what rivers do. Being a river. Expressing the essence of its river-ness.

That is all.

The river is not to blame for Karl’s death.

Here is something I wrote this year about the Tweed River:

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

After we bought Lot 4 at Jarlanbah in Nimbin in 2001, we spent every possible weekend in Nimbin. We’d drive from Brisbane on Friday afternoon. After an hour of freeway driving through the sprawl of outer metropolitan Brisbane, we’d enter the ambit of the caldera of the ancient volcano, Wollumbin, a male initiation site sacred to the local Bundjalung people, glimpsing its dramatic lavender silhouette in the fading light. As we drove, I imagined our new life together in the sub-tropical rainforest. Wollumbin represented hope: every morning, it receives the first rays of sunlight to touch the Australian mainland.

For me, it was a place to nurture our new beginning.

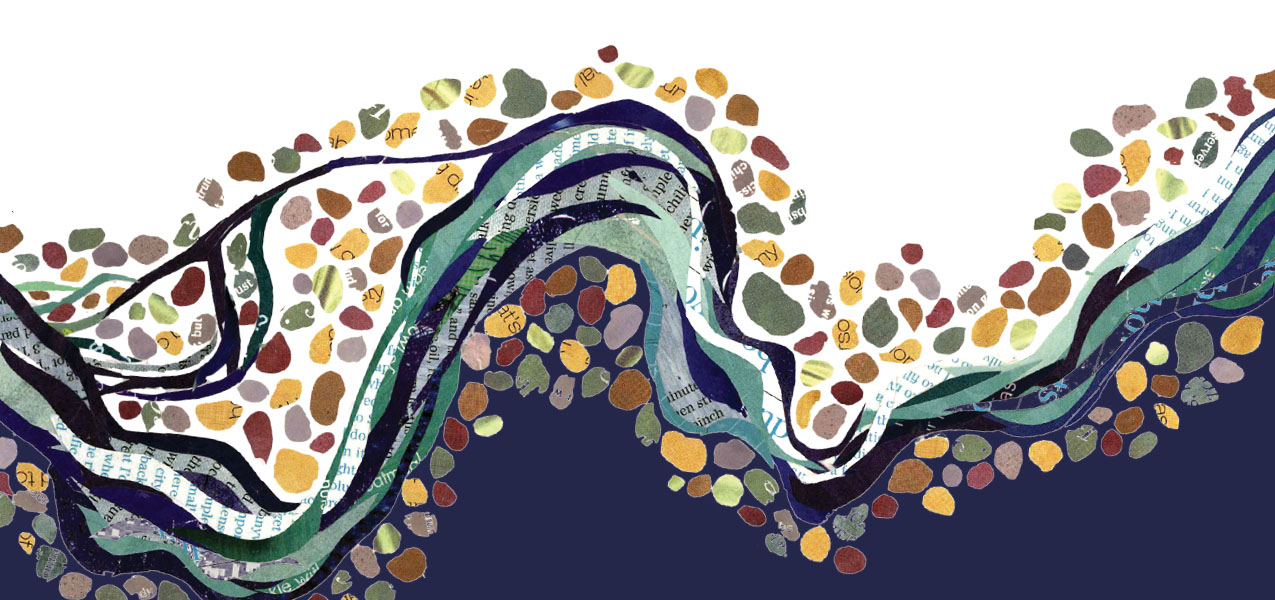

When we reached the tiny village of Uki, the sun would often be setting, and night would fall as Karl navigated the last 40 kilometres of narrow, winding, rural road. Our route, the Kyogle Road, parallels the ancient Tweed River, flowing thirty or forty metres below us. In the Rainbow Region, noted for dramatic storms, the Tweed River often flooded. (Over the years, we’d turn back several times when it washed out the road.) Its meandering course was constantly changing. That river, drawn inexorably seaward, found many ways to reach the ocean. I’d grown up on the banks of a mighty Canadian river and I’d always been attracted to them. (Not Karl: he avoided water at all costs.)

We’d never taken to driving with the radio on, so, with one open window, we drink in the cadences of cicadas, frogs, kookaburras, and the night birds in the deeper reaches of the rainforest. My river meditation draws me to the river’s headwaters, at Lillian Rock, only 10 kilometres from Nimbin. At its source, deep in the valley’s heart, the river begins invisibly, humbly, with the gentlest whisper of intent, a nudge of hopefulness, the suggestion of a few cells pulsing, streaming, vibrating, humming, singing, multiplying, and aligning. Inevitably, the ocean draws the river forth, patiently strengthening and supporting its nascent intentions.

Observing the Tweed River’s seasonal patterns, I sense that eddies and waterholes are a necessary part of its river-ness: moments of hesitation, conditionality, rebelliousness, even. But the ultimate destination of 80 kilometres of presence is the spaciousness of the ocean. The river longs for its flow. Within a broad, deep valley, meandering feels like play. Not all life needs speed and clarity. Slow, silty, muddiness has its place, too. Eddies allow for contemplation, flexibility to bypass obstacles, or an enticing moment of indecision. This river offers forgiveness; all routes lead to the ocean. Calm shallows, coves almost, balance unexpected rough water. But make no mistake: a strong river has significant work to do. Whatever its season, primordial and irrefutable are the forces that draw the river’s waters from its rocky hinterland through sparkling rainforest and expanses of coastal sugarcane to its fulfilment in the embrace of the vast ocean. For, as Kahlil Gibran exclaimed, “life and death are one, even as the river and the sea are one.”(1)

My heart softens as we climb out of the coastal country toward Uki, the portal to our new home. There, as we slow to drive through the tiny village, I call out to Karl, “Nearly home.” He nods.

Nearly home — returning to what would be Karl’s spiritual home.

We have finally landed.